|

And the Winner Is? - Part 2

By Yevgenia Borisova

|

The Moscow Times has documented enough falsification in the March

26 presidential election to question the legitimacy of the vote.

Yevgenia Borisova reports from Dagestan, Saratov, Tatarstan, Ingushetia,

Bashkortostan and Moscow, and by telephone from Novosibirsk, Kursk,

Nizhny Novgorod, Kabardino-Balkariya and Mordovia. With additional

reporting by Gary Peach from Kaliningrad, Nonna Chernyakova from

Vladivostok and Mayerbeck Nunayev from Chechnya.

See No Evil?

Federal elections law gives Russian and foreign organizations broad

powers to observe all voting day activities, and observers are supposed

to prevent the most crude abuses.

But observers were not everywhere. Communist and Yabloko party

observers allege having seen, or heard of, massive fraud, to the tune of

millions of votes. Zyuganov has claimed to have had 7 million votes

stolen from him, quite a lot if Putin won by about 2 million - but the

evidence provided for such claims, while often troubling, is not

complete.

Meanwhile, it's hard to know how seriously to take foreign

observers. Consider the biggest, the Organization for Security and

Cooperation in Europe, which sent a team of about 400 people to observe

both the 1999 Duma elections and then again three months later the

presidential vote. As with other foreign observer groups, about a 10th

of the OSCE teams were "long-term" observers with strong knowledge of

Russia and Russian, who arrived months beforehand to take an in-depth

look at the situation, while the other 380 or so were flown in late in

the game to watch the voting day.

Edouard Brunner, head of the OSCE delegation, told The Moscow Times

a week before the Duma vote that he expected "international observers

will come up with a statement [after the Dec. 19 vote] that the

elections were conducted in a democratic way." They did indeed (with the

exception of the least well-known of the lot, the European Media

Institute, which characterized the Duma vote as "sad" and a step back

from democracy for Russia).

The short-term foreign observers usually include the top officials

like Brunner - and it is they who tend to set the tone of the crucial

morning-after news conferences and press releases.

Following the presidential elections, long-term OSCE observers

interviewed by The Moscow Times, on strict condition of anonymity,

expressed disgust for the cheery tone of the day-after OSCE commentary -

and dissatisfaction that the more thorough, official OSCE report on the

elections - which was published two months later and was harsher and

more informed - got no attention.

"They make the OSCE's press statement on the elections before the

long-term observers - and it's the long-term observers who really know

the story - have actually given their reports," said one long-term OSCE

observer. "They don't actually hear all the evidence before they write

it - and then what happens is, the longer report that the OSCE writes,

which is sometimes more critical, its overall tone is set by the press

statement.

"Because the press statement is the official stamp of approval.

That's what gets quoted in the newspapers ... That's what Putin's people

carry around with them in their hand. Nobody will read the detailed

report."

That detailed report, released May 19, is posted on the OSCE web

site. In it, the OSCE sticks to its initial finding that the elections

were democratic and a step forward for Russia. But the report also cites

anecdotal evidence from the long-term observers similar to stories heard

repeatedly by The Moscow Times - even as the report downplays the

significance of the abuses it chronicles and goes into little detail.

The OSCE report states, for example, that in fully half of all

polling stations visited by OSCE observers, "some of the cumbersome

procedural requirements for the vote count were circumvented in order to

expedite the process."

It also notes that the Communist Party observers in particular had

documented "episodic violations that, in and of themselves, would not

appear to be sufficient to alter the outcome," and then goes on to give

a jargon-softened list:

"For example, sporadic instances of family voting, inclusion of

deceased persons on voter lists, occasional denial of requests to

receive copies of protocols, various abuses of administrative resources,

improper influence of administrative authorities seen to be directing

the work of polling station commissions, expulsion of individual

observers from some sites, incidents of inequities regarding access to

the mass media, distribution of campaign material during the 'silent

period,' etc."

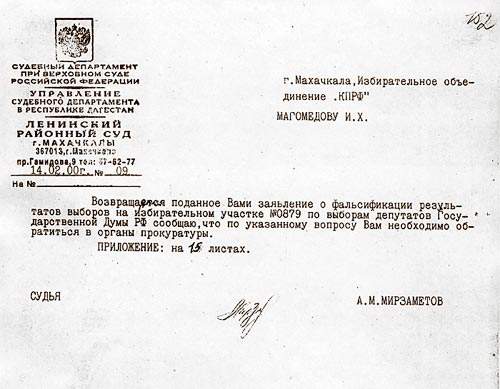

Caught Red-Handed in Dagestan 3: Even more discrepancies between

what was counted and reported locally in Makhachkala, and what was

officially recorded higher up by the territorial commissions.

Why Did They Do It?

"Other allegations were more serious and deserve the full weight of

investigation," the OSCE report continues. "They involved charges that

protocols were falsified, in some instances by reversing or increasing

the vote totals recorded for Putin over Zyuganov."

The report concludes that the OSCE observers "are not in a position

to judge the validity of the complaints raised by the Communist Party

and can draw no conclusions as to the proficiency and seriousness with

which they were reviewed by competent election commissions or the

courts."

Yet the OSCE did in effect reject the validity of those complaints

- when they endorsed the elections as free, fair and democratic. In

similar cases, such as the fraud-tainted April re-election of Peruvian

President Alberto Fujimori, Western observers complained until new

elections were held. The winner, again Fujimori, today enjoys more

legitimacy thanks to the exercise.

"Why did [Western observers] do it [endorse the Putin election as

legitimate]? In obvious support for what they call Russian reforms,"

said Boris Kagarlitsky, a sociologist and political analyst with the

Institute for Comparative Politics. "And of course in support for Putin

as a reformer. It is a credit of trust to Putin and an extension of the

support of the Chubais group," he added, referring to long-running

Western support for Anatoly Chubais, the architect of Russian

privatization programs.

"Many of these organizations, they have as it were a political

statement that they want to make before they go," said an OSCE long-term

observer unhappy with the organization's soothing official findings. "I

thought it was very, very ... totally cynical and unsatisfactory, and if

I had been writing the press statement I'd have given it a different

slant."

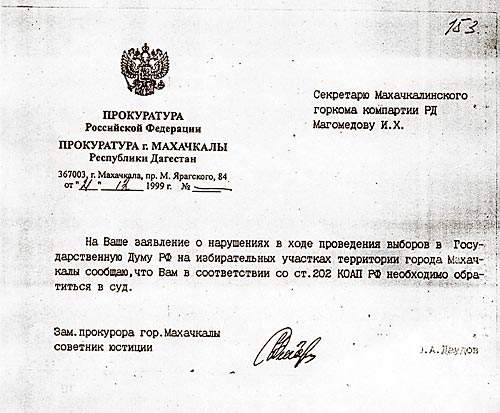

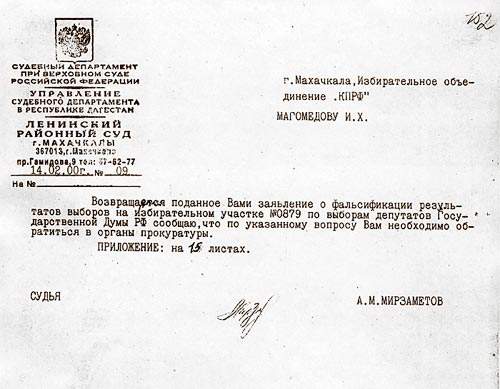

Caught Red-Handed in Dagestan 2: Even more discrepancies between

what was counted and reported locally in Makhachkala, and what was

officially recorded higher up by the territorial commissions.

Who Gave the Orders?

Not one person of those interviewed over the six months since the

election could offer compelling evidence that fraud was part of a

national conspiracy organized on direct orders from anyone in the

Kremlin.

But there is abundant evidence that in some of Russia's 89 regions,

orders to falsify the vote came down directly and formally from the

governors' offices - in a nation where governors from Kaliningrad to

Vladivostok all publicly embraced Putin's political vehicle Unity. And

there are reasons to believe that Kremlin officials might have made

clear, with not-always-subtle hints, that regional leaders were expected

to deliver the Putin vote by hook or by crook.

Consider just the example of the 1995 Duma elections, when

then-Prime Minister Viktor Chernomyrdin angrily and publicly berated

regional governors for not delivering the vote - and even threatened to

engineer the downfall of governors of regions where Our Home Is Russia

did worst.

That the Putin team saw the apparatus of government as subordinate

to their campaign needs is suggested by the composition of the team

itself. According to the OSCE's final report on the March 26 vote, Putin

campaign staff included, among many others, three deputy heads of the

Kremlin administration; top Interior Ministry officials including the

first deputy minister and deputy police chiefs across the nation; top

Railways Ministry officials representing all of the country's major

railroad routes; and top officials from the tax and agriculture

ministries.

"[OSCE observers] in different regions encountered incidents where

campaign materials for the acting president were found in offices of

territorial election commissions," the OSCE report says, referring to

the unit that oversees 20 to 30 polling stations. "Some territorial

commissions acknowledged that they were instructed by the administration

to pick up Putin campaign materials for distribution in their areas.

Corroborating reports were submitted from territorial commissions as far

distant from one another as [Vladivostok] and Kazan.

"In one instance, the chairwoman of a territorial commission

acknowledged that one day earlier, she had received her first specific

order regarding promoting the acting president's campaign. At that time

she had been instructed to pick up campaign literature promoting his

candidacy at the same time as she picked up the ballots for her

territory."

Elections officials were also apparently bullied into making up

results - whether by adding "dead souls" to their count (see sidebar,

page VII) or "correcting" official lower-level results to favor Putin.

Not only were governors apparently bullying the local elections

officials in their fiefdoms, they were leaning on everyone else as well

- from mayors to the heads of schools, factories and collective farms.

The day after the elections, this was suggested in Nizhny Novgorod,

when Governor Ivan Sklyarov - in an angry speech to a hall filled with

squirming officials from across the region that was partially televised

- shouted at heads of districts where Zyuganov did unusually well. "This

post-factum revealed that there were orders given prior to the elections

that they should be organized in a particular way," said Oleg

Kotelnikov, a top Communist Party member in Nizhny Novgorod, by

telephone.

Tales like this can be heard across the nation. Consider Tatarstan:

"[Tatarstan President] Mintimer Sharipovich [Shaimiyev] collected

us, the heads of local governments, and said approximately this: 'If

Primakov had put forward his candidacy, we would call on Tatarstan's

people to vote for him. But as he has declined to do so, today the

republic urges its citizens to vote for Putin," recounted Rashid

Khamadeyev, mayor of the town of Naberezhniye Chelny, located 190

kilometers east of Kazan.

In an interview in the local newspaper Vecherniye Chelny, Mayor

Khamadeyev recalled how Shaimiyev continued his address:

"Today I earnestly urge our leaders to create initiative groups

headed by heads [of enterprises], and to organize public receptions at

every enterprise to support Putin's candidacy.

"Of course if [a local leader] does not desire to do so, he may

refuse. But after the elections, I have a great desire to analyze the

quality of work of each [factory director or local leader]. We will take

the results of each polling station and see how many people came and how

they voted. And we will see how each local leader worked - in whose

favor? And is it worth it to keep him in his post?"

In neighboring Bashkortostan, local government officials in regions

where Putin did worst consistently resigned afterward.

One such official, Ravil Khudaiberdin, who headed the local

government of the Uchaly district - 220 kilometers east of Ufa -

explained his resignation in wonderfully twisted logic in the newspaper

Nash Vybor. In Khudaiberdin's patch of Bashkortostan, Putin won 40.65

percent of the vote and Zyuganov 48.73.

"It's no secret that a major propaganda campaign was part of the

run-up to the elections. A personality was defined who could lead our

country by the way of democratization of our society - V.V. Putin. Our

local government, like others, was explaining who all must vote for, but

our appeals were not heard.

"This means that I and my team were not supported by the residents

of the city and district. Such a result in the elections is a vote of no

confidence in my administration, and that is why I decided to resign."

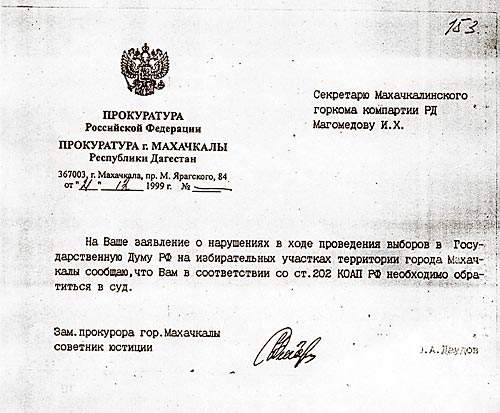

Magomedov appealed to the court and the prosecutor, but they

ignored his complaint.

How Bullying Works

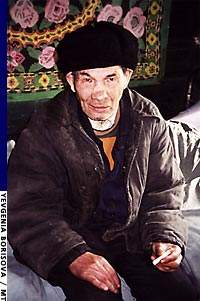

"I wanted to vote for Zhirinovsky," recounted pensioner Pyotr

Filippov, 71. "Zhirinovsky is a good lad, he promised us cheap bread.

But [Valentin] Markov, the head of our village, took away my ballot and

signed it for Putin."

Filippov is an ethnic Chuvash who lives in the Tatarstan village of

Tatarsky Saplyk, about 240 kilometers southeast of Kazan. As he spoke,

sitting on a shabby bed that doubles as a couch, his unemployed son

nodded in agreement. The son, too, had accompanied his father to the

precinct that day and also had wanted to vote for Zhirinovsky - but like

his father he had his ballot taken away and cast for Putin.

Other Tatarsky Saplyk residents recounted similar tales.

"The head of our collective farm told me, 'Sign for Putin,' and

grabbed my pen from me," said Nikolai, a 40-year-old farmer who did not

want his last name published. "But I told him that I wanted to sign for

Zyuganov and grabbed back the pen, quickly marked [the box for] Zyuganov

and put it in the ballot box. He said to me, 'Look, I will get back at

you.'"

But Nikolai said he was not afraid because he has his own business.

"What can he do to me?" he asked rhetorically. "Last year, they

paid me just 300 rubles for the entire year. But now I've found a

private job - I do window frames - and I don't care what he says."

Tatarsky Saplyk is located in the rural Drazhzhanovsky district - a

traditionally Communist patch of Tatarstan not supervised by any

elections observers. Putin won this collective farming region with a

staggering 86.2 percent, while Zyuganov earned just 8.05 percent.

The Communists are not alone in attributing this landslide for

Putin to the persuasive power of "administrative resources" - that

vertical chain of bullying governors set in action when they order their

underlings to bring in the Putin vote or be sacked.

"I think that this [bullying] has affected the final results of the

presidential elections more than even direct falsification of votes,"

said Viktor Sheinis, a professor at the Institute of the World Economy

and International Relations, a branch of the Russian Academy of

Sciences.

Sheinis said regional chieftains easily manipulate the average

rural Russians.

"They look at the peasants like a boa constrictor does at a rabbit.

The level of political culture in our villages is not high, it is not

Moscow - if something happens here, no one will pay attention," he said.

"And if some babushka comes to vote, and she is completely dependent on

the administration chief for getting wood and fodder for her animals -

she will of course vote the way he tells her to."

For years now, collective farms in Tatarstan, Bashkortostan, Kursk,

Mordovia and Dagestan - to name five regions where "administrative

resource" bullying was rampant - have been failing to pay wages on time,

and instead have paid in goods produced at the farms such as wheat,

sugar and hay. These goods are a survival kit for villagers that

supplements what they raise in their own gardens and from their own

domestic animals - and a weapon at times of elections.

"In the village of Permiyevo, where I am from, the head of the

collective farm told villagers that if they vote for Zyuganov, he would

find out - and they would not get tractors for sowing, or wood, or

food," said Valentina Lyukzayeva, a secretary of the Communist Party in

Mordovia, in a telephone interview. "The villagers, most of whom are old

women, of course got frightened and voted for Putin."

In some cases, not just voters but even official observers were

told to choose between obedience and hunger.

"In many polling stations our observers were threatened that they

would not receive food and fodder packages," said Rinat Gabidullin, a

secretary of Bashkortostan's Communist Party.

Gabidullin argues that villagers as a class across the nation were

simply excluded from the democratic process. But it's not just villagers

who are so weak: All state employees, from education workers to police

officers to city hall secretaries, have proven in interviews to have

been vulnerable to such pressure. A feature common to some of the

worst-run elections commissions, notably in Dagestan and

Kabardino-Balkariya, was that they would be made up almost entirely from

the staff of a particular school or institute of higher learning - and

chaired by the head of the institute.

Magomedov appealed to the court and the prosecutor, but they

ignored his complaint.

The Caterpillar

This report has so far been a discussion of fraud introduced within

the state apparatus - either by abusing state power to bully voters, or

by pressuring elections officials to one way or another misreport or

skew results.

But fraud was also introduced from outside the system - most

spectacularly in Tatarstan - by a crawling system of ballot-box stuffing

that came to be referred to as "the caterpillar." This practice was so

widespread that Vladimir Shevchuk, head of the Tatarstan Elections-2000

Press Center, not only admitted it had existed, he even explained how it

works.

"There are people standing near the elections precincts and when

they see a voter coming up, they offer him or her 50 rubles or a 100

rubles so that he or she takes a pre-filled-in ballot to drop in the

box, and then returns with a blank ballot," Shevchuk said. "Then [the

fraudsters] fill in the new clean ballot and offer it to the next

voter."

Shevchuk added that in December, during the State Duma elections,

even President Shaimiyev's spokesman Irek Murtazin was asked to play the

caterpillar game. And in a telephone interview, Murtazin confirmed that

he had been given 50 rubles for stuffing a ballot - although he added

that he had cheated the cheaters, and that the ballot in question had

not been for the Duma elections but for parallel elections to the

Tatarstan legislative assembly.

"I took their ballot and put an additional mark on it - thus

spoiling it - and took them out a clean ballot. I wanted to vote against

everyone anyway," Murtazin said, laughing.

The caterpillar might have been nearly foolproof. But not everyone

was content to earn just 50 rubles. Three people were arrested at

separate Tatarstan polling stations for trying to stuff large packets of

ballots into the ballot box - always in favor of Putin, but sometimes

also in favor of a candidate in local legislative elections, said Alexei

Afanasiev, a legal adviser to the Communist Party in Tatarstan.

Afanasiev said nothing seems to have come of the investigations

into those arrests, though all three still await trial.

One of those ballot-box stuffers was caught by Felix Rashidov, a

member of the elections commission at Kazan's 263rd voting precinct.

"Suddenly one voter approached us and told us to come quickly to

the ballot box," Rashidov recounted in an interview. "We saw a

Caucasian-looking man put a large pack of ballots into the box!

"We immediately grabbed him and called the police," Rashidov said.

"An official report was made, the ballot box was opened and the ballots

were taken out. There were two lots [bundled together] - 12 ballots were

filled in for Putin and 12 for a local candidate to Tatarstan's

legislative assembly."

Who paid for the ballots to be stuffed? It's hard to say. But even

here, there are signs that ballot-box stuffing can be traced back to

"administrative resources" abuses. In Dagestan, for example, an

elections commission member for Makhachkala's 931st voting precinct said

she learned a local school had been pressuring parents of students to

sneak in ballots for Putin and stuff them into the box.

"After election day, two pairs of parents brought me two small

packets of ballots - three ballots in each packet - that they said they

had been given by teachers of their children, to stuff into the ballot

box along with their own [votes]."